Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Discuss the applications of statics in real life

- State and discuss various problem-solving strategies in statics

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

- 3.F.1.1 The student is able to use representations of the relationship between force and torque. (S.P. 1.4)

- 3.F.1.2 The student is able to compare the torques on an object caused by various forces. (S.P. 1.4)

- 3.F.1.3 The student is able to estimate the torque on an object caused by various forces in comparison to other situations. (S.P. 2.3)

- 3.F.1.4 The student is able to design an experiment and analyze data testing a question about torques in a balanced rigid system. (S.P. 4.1, 4.2, 5.1)

- 3.F.1.5 The student is able to calculate torques on a two-dimensional system in static equilibrium by examining a representation or model, such as a diagram or physical construction. (S.P. 1.4, 2.2)

Statics can be applied to a variety of situations, ranging from raising a drawbridge to bad posture and back strain. We begin with a discussion of problem-solving strategies specifically used for statics. Since statics is a special case of Newton's laws, both the general problem-solving strategies and the special strategies for Newton's laws, discussed in Problem-solving Strategies, still apply.

Problem-solving Strategy: Static-equilibrium Situations

- The first step is to determine whether or not the system is in static equilibrium. This condition is always the case when the acceleration of the system is zero and accelerated rotation does not occur.

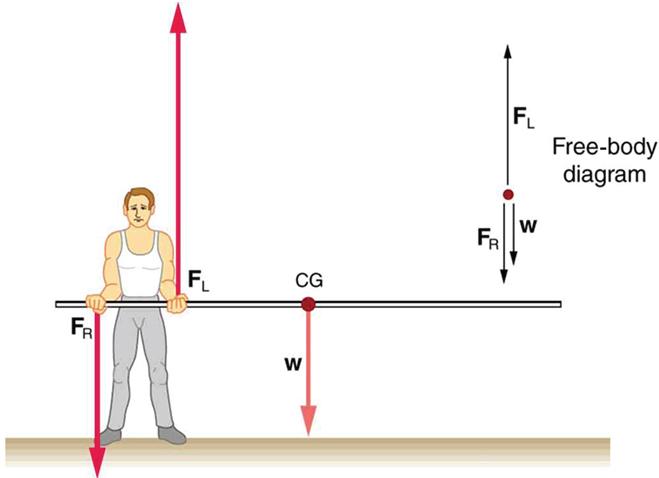

- It is particularly important to draw a free body diagram for the system of interest. Carefully label all forces, and note their relative magnitudes, directions, and points of application whenever these are known.

- Solve the problem by applying either or both of the conditions for equilibrium, represented by the equations and , depending on the list of known and unknown factors. If the second condition is involved, choose the pivot point to simplify the solution. Any pivot point can be chosen, but the most useful ones cause torques by unknown forces to be zero. Torque is zero if the force is applied at the pivot (then ) or along a line through the pivot point (then ). Always choose a convenient coordinate system for projecting forces.

- Check the solution to see if it is reasonable by examining the magnitude, direction, and units of the answer. The importance of this last step never diminishes, although in unfamiliar applications, it is usually more difficult to judge reasonableness. These judgments become progressively easier with experience.

Now let us apply this problem-solving strategy for the pole vaulter shown in the three figures below. The pole is uniform and has a mass of 5 kg. In Figure 9.20, the pole's cg lies halfway between the vaulter's hands. It seems reasonable that the force exerted by each hand is equal to half the weight of the pole, or 24.5 N. This obviously satisfies the first condition for equilibrium . The second condition is also satisfied, as we can see by choosing the cg to be the pivot point. The weight exerts no torque about a pivot point located at the cg, since it is applied at that point and its lever arm is zero. The equal forces exerted by the hands are equidistant from the chosen pivot, and so they exert equal and opposite torques. Similar arguments hold for other systems where supporting forces are exerted symmetrically about the cg. For example, the four legs of a uniform table each support one-fourth of its weight.

In Figure 9.20, a pole vaulter holding a pole with its cg halfway between his hands is shown. Each hand exerts a force equal to half the weight of the pole, . The pole vaulter moves the pole to his left, and the forces that the hands exert are no longer equal. See Figure 9.20. If the pole is held with its cg to the left of the person, then he must push down with his right hand and up with his left. The forces he exerts are larger here, because they are in opposite directions and the cg is at a long distance from either hand.

Similar observations can be made using a meter stick held at different locations along its length.

If the pole vaulter holds the pole as shown in Figure 9.21, the situation is not as simple. The total force he exerts is still equal to the weight of the pole, but it is not evenly divided between his hands. (If , then the torques about the cg would not be equal, since the lever arms are different.) Logically, the right hand should support more weight, since it is closer to the cg. In fact, if the right hand is moved directly under the cg, it will support all the weight. This situation is exactly analogous to two people carrying a load; the one closer to the cg carries more of its weight. Finding the forces and is straightforward, as the next example shows.

If the pole vaulter holds the pole from near the end of the pole (Figure 9.22), the direction of the force applied by the right hand of the vaulter reverses its direction.

Example 9.2 What Force is Needed to Support a Weight Held Near its CG?

For the situation shown in Figure 9.20, calculate (a) , the force exerted by the right hand, and (b) , the force exerted by the left hand. The hands are 0.900 m apart, and the cg of the pole is 0.600 m from the left hand.

Strategy

Figure 9.20 includes a free-body diagram for the pole, the system of interest. There is not enough information to use the first condition for equilibrium ), since two of the three forces are unknown, and the hand forces cannot be assumed to be equal in this case. There is enough information to use the second condition for equilibrium if the pivot point is chosen to be at either hand, thereby making the torque from that hand zero. We choose to locate the pivot at the left hand in this part of the problem to eliminate the torque from the left hand.

Solution for (a)

There are now only two nonzero torques: those from the gravitational force () and from the push or pull of the right hand (). Stating the second condition in terms of clockwise and counterclockwise torques,

or the algebraic sum of the torques is zero.

Here, this is

since the weight of the pole creates a counterclockwise torque and the right hand counters with a clockwise torque Using the definition of torque, , noting that and substituting known values, we obtain

Thus,

Solution for (b)

The first condition for equilibrium is based on the free body diagram in the figure. This implies that by Newton's second law,

From this we can conclude that

Solving for , we obtain

Discussion

is seen to be exactly half of , as we might have guessed, since is applied twice as far from the cg as .

If the pole vaulter holds the pole as he might at the start of a run, shown in Figure 9.22, the forces change again. Both are considerably greater, and one force reverses direction.

Take-home Experiment

This is an experiment to perform while standing in a bus or a train. Stand facing sideways. How do you move your body to readjust the distribution of your mass as the bus accelerates and decelerates? Now stand facing forward. How do you move your body to readjust the distribution of your mass as the bus accelerates and decelerates? Why is it easier and safer to stand facing sideways rather than forward? Note For your safety (and those around you), make sure you are holding onto something while you carry out this activity!