Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

In this section, you will explore the following questions:

- What are the different types of hormones?

- What is the role of hormones in maintaining homeostasis?

Connection for AP® Courses

Connection for AP® Courses

Much information about the various organ systems of animals is not within the scope for AP®. The endocrine system, however, was selected for in-depth study because an animal’s ability to detect, transmit and respond to information is critical to survival. The endocrine and nervous systems work together to maintain homeostasis and adjust physiological activity when external or internal environmental conditions change. The nervous system works by generating action potentials along neurons; the endocrine system uses chemical messengers called hormones that are released from glands, travel to target cells, and elicit a response by the target cell. For AP® you are not expected to memorize a laundry list of the various endocrine glands, their hormones, and the effects of each hormone. You should be able to interpret, however, a diagram that shows the activity of a hormonal signal. We will briefly describe a few of these examples in How Hormones Work.

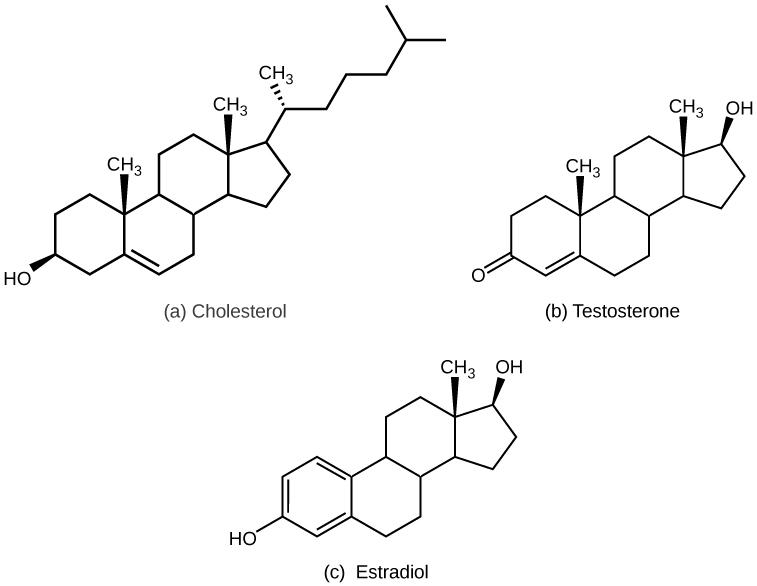

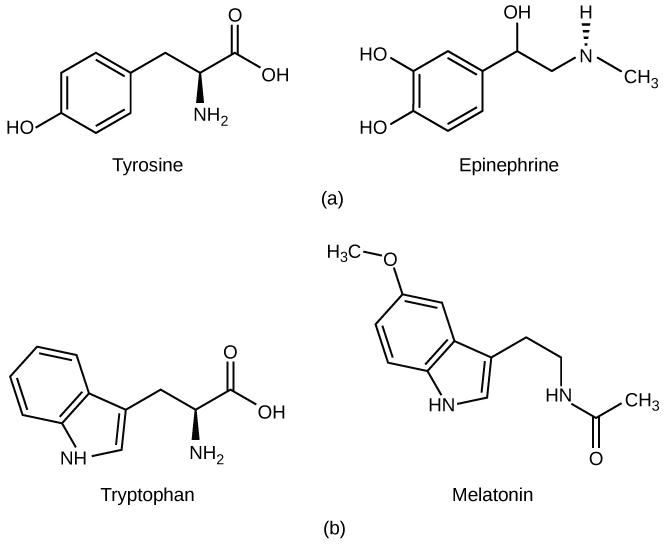

There are three types of hormones classified based on molecular structure and properties. We explored structure/function relationships at the molecular level in the chapter on Biological Macromolecules. Lipid-derived hormones are lipid-soluble and can diffuse across cell membranes because they are non-polar. Most lipid hormones are derived from cholesterol; examples include steroids such as estrogen and testosterone. Because lipid hormones can diffuse across cell membranes, their receptors are located in the cytoplasm of target cells. The amino acid-derived hormones are relatively small molecules derived from the amino acids tyrosine and tryptophan; examples include epinephrine, norepinephrine, thyroxin, and melatonin. Peptide hormones such as oxytocin and growth hormone consist of polypeptide chains of amino acids. Because these hormones are water-soluble and insoluble in lipids, they cannot pass through the plasma membrane of cells; their receptors are found on the surface of the target cells.

Information presented and the examples highlighted in the section support concepts outlined in Big Idea 3 and Big Idea 4 of the AP® Biology Curriculum Framework. The AP® Learning Objectives listed in the Curriculum Framework provide a transparent foundation for the AP® Biology course, an inquiry-based laboratory experience, instructional activities, and AP® exam questions. A learning objective merges required content with one or more of the seven science practices.

| Big Idea 3 | Living systems store, retrieve, transmit, and respond to information essential to life processes. |

| Enduring Understanding 3.D | Cells communicate by generating, transmitting, and receiving chemical signals. |

| Essential Knowledge | 3.D.1 Cell communication processes share common features that reflect a shared evolutionary history. |

| Science Practice | 6.2 The student can construct explanations of phenomena based on evidence produced through scientific practices. |

| Learning Objective | 3.33 The student is able to use representations and models to describe features of a cell signaling pathway. |

| Big Idea 4 | Biological systems interact, and these systems and their interactions possess complex properties. |

| Enduring Understanding 4.A | Interactions within biological systems lead to complex properties. |

| Essential Knowledge | 4.A.1 The subcomponents of biological molecules and their sequence determine the properties of that molecule. |

| Science Practice | 7.1 The student can connect phenomena and models across spatial and temporal scales. |

| Learning Objective | 4.1 The student is able to explain the connection between the sequence and subcomponents of a biological polymer and its properties. |

Maintaining homeostasis within the body requires the coordination of many different systems and organs. Communication between neighboring cells, and between cells and tissues in distant parts of the body, occurs through the release of chemicals called hormones. Hormones are released into body fluids—usually blood—that carry these chemicals to their target cells. At the target cells, which are cells that have a receptor for a signal or ligand from a signal cell, the hormones elicit a response. The cells, tissues, and organs that secrete hormones make up the endocrine system. Examples of glands of the endocrine system include the adrenal glands, which produce hormones such as epinephrine and norepinephrine that regulate responses to stress, and the thyroid gland, which produces thyroid hormones that regulate metabolic rates.

Although there are many different hormones in the human body, they can be divided into three classes based on their chemical structure: lipid-derived, amino acid-derived, and peptide—peptide and proteins—hormones. One of the key distinguishing features of lipid-derived hormones is that they can diffuse across plasma membranes whereas the amino acid-derived and peptide hormones cannot.

Lipid-Derived or Lipid-Soluble Hormones

Lipid-Derived or Lipid-Soluble Hormones

Most lipid hormones are derived from cholesterol and thus are structurally similar to it, as illustrated in Figure 28.2. The primary class of lipid hormones in humans is the steroid hormones. Chemically, these hormones are usually ketones or alcohols; their chemical names will end in -ol for alcohols or -one for ketones. Examples of steroid hormones include estradiol, which is an estrogen, or female sex hormone, and testosterone, which is an androgen, or male sex hormone. These two hormones are released by the female and male reproductive organs, respectively. Other steroid hormones include aldosterone and cortisol, which are released by the adrenal glands along with some other types of androgens. Steroid hormones are insoluble in water, and they are transported by transport proteins in blood. As a result, they remain in circulation longer than peptide hormones. For example, cortisol has a half-life of 60-90 minutes, while epinephrine, an amino acid derived-hormone, has a half-life of approximately one minute.

Amino Acid-Derived Hormones

Amino Acid-Derived Hormones

The amino acid-derived hormones are relatively small molecules that are derived from the amino acids tyrosine and tryptophan, shown in Figure 28.3. If a hormone is amino acid-derived, its chemical name will end in -ine. Examples of amino acid-derived hormones include epinephrine and norepinephrine, which are synthesized in the medulla of the adrenal glands, and thyroxine, which is produced by the thyroid gland. The pineal gland in the brain makes and secretes melatonin, which regulates sleep cycles.

Peptide Hormones

Peptide Hormones

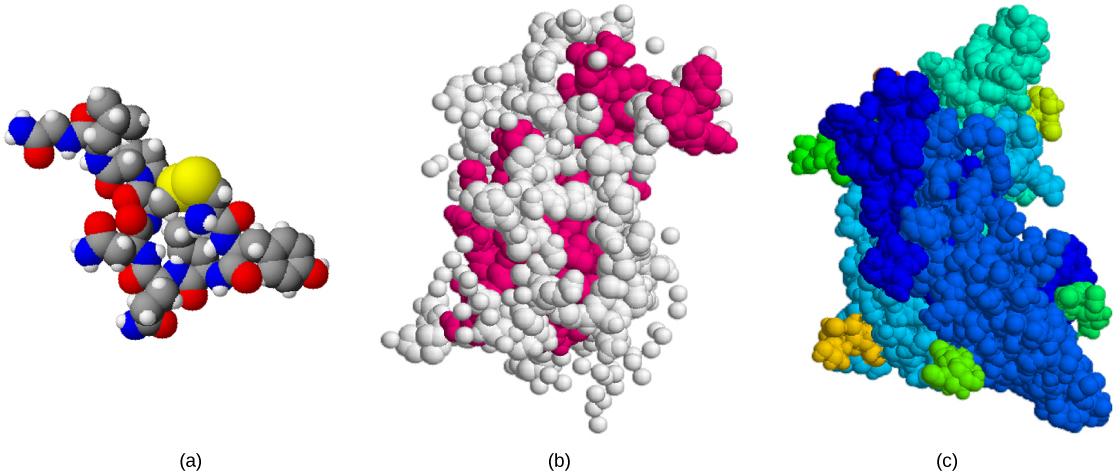

The structure of peptide hormones is that of a polypeptide chain, that is, a chain of amino acids). The peptide hormones include molecules that are short polypeptide chains, such as antidiuretic hormone and oxytocin produced in the brain and released into the blood in the posterior pituitary gland. This class also includes small proteins, like growth hormones produced by the pituitary, and large glycoproteins such as follicle-stimulating hormone produced by the pituitary. Figure 28.4 illustrates these peptide hormones.

Secreted peptides like insulin are stored within vesicles in the cells that synthesize them. They are then released in response to stimuli such as high blood glucose levels in the case of insulin. Amino acid-derived and polypeptide hormones are water-soluble and insoluble in lipids. These hormones cannot pass through plasma membranes of cells; therefore, their receptors are found on the surface of the target cells.

Science Practice Connection for AP® Courses

Think About It

Although there are many different hormones in the human body, they can be classified based on their chemical structure. What one factor distinguishes them?

Career Connection

Endocrinologist

An endocrinologist is a medical doctor who specializes in treating disorders of the endocrine glands, hormone systems, and glucose and lipid metabolic pathways. An endocrine surgeon specializes in the surgical treatment of endocrine diseases and glands. Some of the diseases that are managed by endocrinologists: disorders of the pancreas, such as diabetes mellitus, disorders of the pituitary, such as gigantism, acromegaly, and pituitary dwarfism, disorders of the thyroid gland, such as goiter and Graves’ disease, and disorders of the adrenal glands, such as Cushing’s disease and Addison’s disease.

Endocrinologists are required to assess patients and diagnose endocrine disorders through extensive use of laboratory tests. Many endocrine diseases are diagnosed using tests that stimulate or suppress endocrine organ functioning. Blood samples are then drawn to determine the effect of stimulating or suppressing an endocrine organ on the production of hormones. For example, to diagnose diabetes mellitus, patients are required to fast for 12-24 hours. They are then given a sugary drink, which stimulates the pancreas to produce insulin to decrease blood glucose levels. A blood sample is taken one to two hours after the sugar drink is consumed. If the pancreas is functioning properly, the blood glucose level will be within a normal range. Another example is the A1C test, which can be performed during blood screening. The A1C test measures average blood glucose levels over the past two to three months by examining how well the blood glucose is being managed over a long time.

Once a disease has been diagnosed, endocrinologists can prescribe lifestyle changes and/or medications to treat the disease. Some cases of diabetes mellitus can be managed by exercise, weight loss, and a healthy diet; in other cases, medications may be required to enhance insulin release. If the disease cannot be controlled by these means, the endocrinologist may prescribe insulin injections.

In addition to clinical practice, endocrinologists may also be involved in primary research and development activities. For example, ongoing islet transplant research is investigating how healthy pancreas islet cells may be transplanted into diabetic patients. Successful islet transplants may allow patients to stop taking insulin injections.