Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- List the three properties of a conductor in electrostatic equilibrium

- Explain the effect of an electric field on free charges in a conductor

- Explain why no electric field may exist inside a conductor

- Describe the electric field surrounding Earth

- Explain what happens to an electric field applied to an irregular conductor

- Describe how a lightning rod works

- Explain how a metal car may protect passengers inside from the dangerous electric fields caused by a downed line touching the car

The information presented in this section supports the following AP learning objectives:

- 2.C.3.1 The student is able to explain the inverse square dependence of the electric field surrounding a spherically symmetric electrically charged object.

- 2.C.5.1 The student is able to create representations of the magnitude and direction of the electric field at various distances—small compared to plate size—from two electrically charged plates of equal magnitude and opposite signs and is able to recognize that the assumption of uniform field is not appropriate near edges of plates.

Conductors contain free charges that move easily. When excess charge is placed on a conductor or the conductor is put into a static electric field, charges in the conductor quickly respond to reach a steady state called electrostatic equilibrium.

Figure 1.28 shows the effect of an electric field on free charges in a conductor. The free charges move until the field is perpendicular to the conductor's surface. There can be no component of the field parallel to the surface in electrostatic equilibrium, since, if there were, it would produce further movement of charge. A positive free charge is shown, but free charges can be either positive or negative and are, in fact, negative in metals. The motion of a positive charge is equivalent to the motion of a negative charge in the opposite direction.

A conductor placed in an electric field will be polarized. Figure 1.29 shows the result of placing a neutral conductor in an originally uniform electric field. The field becomes stronger near the conductor but entirely disappears inside it.

Misconception Alert: Electric Field Inside a Conductor

Excess charges placed on a spherical conductor repel and move until they are evenly distributed, as shown in Figure 1.30. Excess charge is forced to the surface until the field inside the conductor is zero. Outside the conductor, the field is exactly the same as if the conductor were replaced by a point charge at its center equal to the excess charge.

Properties of a Conductor in Electrostatic Equilibrium

- The electric field is zero inside a conductor.

- Just outside a conductor, the electric field lines are perpendicular to its surface, ending or beginning on charges on the surface.

- Any excess charge resides entirely on the surface or surfaces of a conductor.

The properties of a conductor are consistent with the situations already discussed and can be used to analyze any conductor in electrostatic equilibrium. This can lead to some interesting new insights, such as described below.

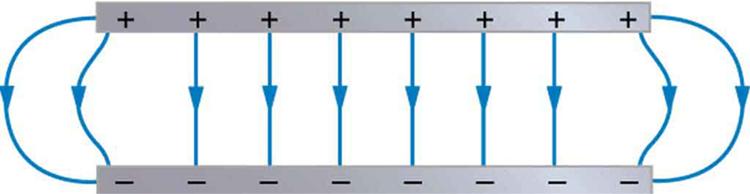

How can a very uniform electric field be created? Consider a system of two metal plates with opposite charges on them, as shown in Figure 1.31. The properties of conductors in electrostatic equilibrium indicate that the electric field between the plates will be uniform in strength and direction. Except near the edges, the excess charges distribute themselves uniformly, producing field lines that are uniformly spaced—hence uniform in strength—and perpendicular to the surfaces—hence uniform in direction, since the plates are flat. The edge effects are less important when the plates are close together.

Earth's Electric Field

Earth's Electric Field

A near uniform electric field of approximately 150 N/C, directed downward, surrounds Earth, with the magnitude increasing slightly as we get closer to the surface. What causes the electric field? At around 100 km above the surface of Earth, we have a layer of charged particles, called the ionosphere. The ionosphere is responsible for a range of phenomena including the electric field surrounding Earth. In fair weather the ionosphere is positive and Earth largely negative, maintaining the electric field (Figure 1.32(a)).

In storm conditions clouds form and localized electric fields can be larger and reversed in direction (Figure 1.32(b)). The exact charge distributions depend on the local conditions, and variations of Figure 1.32(b) are possible.

If the electric field is sufficiently large, the insulating properties of the surrounding material break down and it becomes conducting. For air this occurs at around N/C. Air ionizes ions and electrons recombine, and we get discharge in the form of lightning sparks and corona discharge.

Electric Fields on Uneven Surfaces

Electric Fields on Uneven Surfaces

So far we have considered excess charges on a smooth, symmetrical conductor surface. What happens if a conductor has sharp corners or is pointed? Excess charges on a nonuniform conductor become concentrated at the sharpest points. Additionally, excess charge may move on or off the conductor at the sharpest points.

To see how and why this happens, consider the charged conductor in Figure 1.33. The electrostatic repulsion of like charges is most effective in moving them apart on the flattest surface, and so they become least concentrated there. This is because the forces between identical pairs of charges at either end of the conductor are identical, but the components of the forces parallel to the surfaces are different. The component parallel to the surface is greatest on the flattest surface and, hence, more effective in moving the charge.

The same effect is produced on a conductor by an externally applied electric field, as seen in Figure 1.33 (c). Since the field lines must be perpendicular to the surface, more of them are concentrated on the most curved parts.

Applications of Conductors

Applications of Conductors

On a very sharply curved surface, such as shown in Figure 1.34, the charges are so concentrated at the point that the resulting electric field can be great enough to remove them from the surface. This can be useful.

Lightning rods work best when they are most pointed. The large charges created in storm clouds induce an opposite charge on a building that can result in a lightning bolt hitting the building. The induced charge is bled away continually by a lightning rod, preventing the more dramatic lightning strike.

Of course, we sometimes wish to prevent the transfer of charge rather than to facilitate it. In that case, the conductor should be very smooth and have as large a radius of curvature as possible (see Figure 1.35). Smooth surfaces are used on high-voltage transmission lines, for example, to avoid leakage of charge into the air.

Another device that makes use of some of these principles is a Faraday cage. This is a metal shield that encloses a volume. All electrical charges will reside on the outside surface of this shield, and there will be no electrical field inside. A Faraday cage is used to prohibit stray electrical fields in the environment from interfering with sensitive measurements, such as the electrical signals inside a nerve cell.

During electrical storms if you are driving a car, it is best to stay inside the car as its metal body acts as a Faraday cage with zero electrical field inside. If in the vicinity of a lightning strike, its effect is felt on the outside of the car and the inside is unaffected, provided you remain totally inside. This is also true if an active hot electrical wire was broken in a storm or an accident and fell on your car.