Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Define and discuss fluorescence

- Define metastable

- Describe how laser emission is produced

- Explain population inversion

- Define and discuss holography

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

- 1.A.5.1 The student is able to model verbally or visually the properties of a system based on its substructure and to relate this to changes in the system properties over time as external variables are changed. (S.P. 1.1, 7.1)

- 1.A.5.2 The student is able to construct representations of how the properties of a system are determined by the interactions of its constituent substructures. (S.P. 1.1, 1.4, 7.1)

- 7.C.4.1 The student is able to construct or interpret representations of transitions between atomic energy states involving the emission and absorption of photons. (S.P. 1.1, 1.2)

Many properties of matter and phenomena in nature are directly related to atomic energy levels and their associated excitations and de-excitations. The color of a rose, the output of a laser, and the transparency of air are but a few examples (see Figure 13.30). While it may not appear that glow-in-the-dark pajamas and lasers have much in common, they are in fact different applications of similar atomic de-excitations.

The color of a material is due to the ability of its atoms to absorb certain wavelengths while reflecting or reemitting others. A simple red material, for example a tomato, absorbs all visible wavelengths except red. This is because the atoms of its hydrocarbon pigment, lycopene, have levels separated by a variety of energies corresponding to all visible photon energies except red. Air is another interesting example. It is transparent to visible light, because there are few energy levels that visible photons can excite in air molecules and atoms. Visible light, thus, cannot be absorbed. Furthermore, visible light is only weakly scattered by air, because visible wavelengths are so much greater than the sizes of the air molecules and atoms. Light must pass through kilometers of air to scatter enough to cause red sunsets and blue skies.

Real World Connections: The Tomato

Let us consider the properties of a tomato from two different perspectives. When we try to explain the color of a tomato, we must consider the tomato as a system with properties that depend on its internal structure and the interactions between various parts. The internal structure of the tomato, specifically, the behavior of its pigment molecules, is very important and must be understood. Unlike a hydrogen atom, the energy level structure of a pigment molecule in a tomato is much more complicated. There are a very large number of energy levels, and the energy differences between these levels correspond to many different parts/colors of the visible spectrum, except for red.

So the photons that can be absorbed by these pigment molecules include every energy or wavelength in the visible spectrum except energies or wavelengths in the red part of the spectrum. Because these molecules absorb most of the visible photons, but reflect red photons, the color of the tomato appears red to our eyes. Without understanding the internal structure of the tomato pigment system, we would have no way of explaining its color.

Now consider a tomato in free fall. It accelerates toward Earth at a rate of 9.8 m/s2, and we can say this with confidence without knowing anything about the internal structure of the tomato. In this case, we refer to the tomato as an object rather than a system. We only need to know the macroscopic properties of the tomato—its mass—to understand the force acting on the tomato.

Fluorescence and Phosphorescence

Fluorescence and Phosphorescence

The ability of a material to emit various wavelengths of light is similarly related to its atomic energy levels. Figure 13.31 shows a scorpion illuminated by a UV lamp, sometimes called a black light. Some rocks also glow in black light, the particular colors being a function of the rock’s mineral composition. Black lights are also used to make certain posters glow.

In the fluorescence process, an atom is excited to a level several steps above its ground state by the absorption of a relatively high-energy UV photon. This is called atomic excitation. Once it is excited, the atom can de-excite in several ways, one of which is to re-emit a photon of the same energy as excited it, a single step back to the ground state. This is called atomic de-excitation. All other paths of de-excitation involve smaller steps, in which lower-energy—longer wavelength—photons are emitted. Some of these may be in the visible range, such as for the scorpion in Figure 13.31. Fluorescence is defined to be any process in which an atom or molecule, excited by a photon of a given energy, de-excites by emission of a lower-energy photon.

Fluorescence can be induced by many types of energy input. Fluorescent paint, dyes, and even soap residues in clothes make colors seem brighter in sunlight by converting some UV into visible light. X-rays can induce fluorescence, as is done in X-ray fluoroscopy to make brighter visible images. Electric discharges can induce fluorescence, as in so-called neon lights and in gas-discharge tubes that produce atomic and molecular spectra. Common fluorescent lights use an electric discharge in mercury vapor to cause atomic emissions from mercury atoms. The inside of a fluorescent light is coated with a fluorescent material that emits visible light over a broad spectrum of wavelengths. By choosing an appropriate coating, fluorescent lights can be made more like sunlight or like the reddish glow of candlelight, depending on needs. Fluorescent lights are more efficient in converting electrical energy into visible light than incandescent filaments—about four times as efficient—the blackbody radiation of which is primarily in the infrared due to temperature limitations.

This atom is excited to one of its higher levels by absorbing a UV photon. It can de-excite in a single step, re-emitting a photon of the same energy, or in several steps. The process is called fluorescence if the atom de-excites in smaller steps, emitting energy different from that which excited it. Fluorescence can be induced by a variety of energy inputs, such as UV, X-rays, and electrical discharge.

The spectacular Waitomo caves on North Island in New Zealand provide a natural habitat for glow-worms. The glow-worms hang up to 70 silk threads of about 30 or 40 cm each to trap prey that fly towards them in the dark. The fluorescence process is very efficient, with nearly 100 percent of the energy input turning into light. In comparison, fluorescent lights are about 20 percent efficient.

Fluorescence has many uses in biology and medicine. It is commonly used to label and follow a molecule within a cell. Such tagging allows one to study the structure of DNA and proteins. Fluorescent dyes and antibodies are usually used to tag the molecules, which are then illuminated with UV light and their emission of visible light is observed. Since the fluorescence of each element is characteristic, identification of elements within a sample can be done this way.

Figure 13.32 shows a commonly used fluorescent dye called fluorescein. Below that, Figure 13.33 reveals the diffusion of a fluorescent dye in water by observing it under UV light.

Nano-Crystals

Recently, a new class of fluorescent materials has appeared—nano-crystals. These are single-crystal molecules less than 100 nm in size. The smallest of these are called quantum dots. These semiconductor indicators are very small (2–6 nm) and provide improved brightness. They also have the advantage that all colors can be excited with the same incident wavelength. They are brighter and more stable than organic dyes and have a longer lifetime than conventional phosphors. They have become an excellent tool for long-term studies of cells, including migration and morphology (Figure 13.34).

Once excited, an atom or molecule will usually spontaneously de-excite quickly. The electrons raised to higher levels are attracted to lower ones by the positive charge of the nucleus. Spontaneous de-excitation has a very short mean lifetime of typically about However, some levels have significantly longer lifetimes, ranging up to milliseconds to minutes or even hours. These energy levels are inhibited and are slow in de-exciting because their quantum numbers differ greatly from those of available lower levels. Although these level lifetimes are short in human terms, they are many orders of magnitude longer than is typical and, thus, are said to be metastable, meaning relatively stable. Phosphorescence is the de-excitation of a metastable state. Glow-in-the-dark materials, such as luminous dials on some watches and clocks and on children’s toys and pajamas, are made of phosphorescent substances. Visible light excites the atoms or molecules to metastable states that decay slowly, releasing the stored excitation energy partially as visible light. In some ceramics, atomic excitation energy can be frozen in after the ceramic has cooled from its firing. It is very slowly released, but the ceramic can be induced to phosphoresce by heating—a process called thermoluminescence. Since the release is slow, thermoluminescence can be used to date antiquities. The less light emitted, the older the ceramic (see Figure 13.35).

Lasers

Lasers

Lasers today are commonplace. Lasers are used to read bar codes at stores and in libraries, laser shows are staged for entertainment, laser printers produce high-quality images at relatively low cost, and lasers send prodigious numbers of telephone messages through optical fibers. Among other things, lasers are also employed in surveying, weapons guidance, retinal welding, and for reading music CDs and computer CD-ROMs.

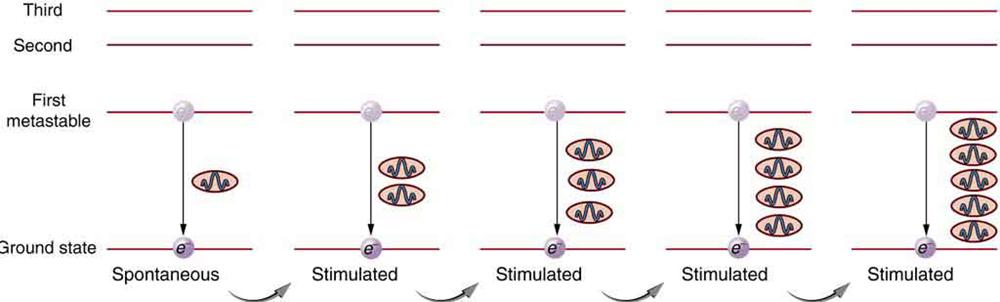

Why do lasers have so many varied applications? The answer is that lasers produce single-wavelength EM radiation that is also very coherent—that is, the emitted photons are in phase. Laser output can, thus, be more precisely manipulated than incoherent mixed-wavelength EM radiation from other sources. The reason laser output is so pure and coherent is based on how it is produced, which in turn depends on a metastable state in the lasing material. Suppose a material had the energy levels shown in Figure 13.36. When energy is put into a large collection of these atoms, electrons are raised to all possible levels. Most return to the ground state in less than about but those in the metastable state linger. This includes those electrons originally excited to the metastable state and those that fell into it from above. It is possible to get a majority of the atoms into the metastable state, a condition called a population inversion.

Once a population inversion is achieved, a very interesting thing can happen, as shown in Figure 13.37. An electron spontaneously falls from the metastable state, emitting a photon. This photon finds another atom in the metastable state and stimulates it to decay, emitting a second photon of the same wavelength and in phase with the first, and so on. Stimulated emission is the emission of electromagnetic radiation in the form of photons of a given frequency, triggered by photons of the same frequency. For example, an excited atom, with an electron in an energy orbit higher than normal, releases a photon of a specific frequency when the electron drops back to a lower energy orbit. If this photon then strikes another electron in the same high-energy orbit in another atom, another photon of the same frequency is released. The emitted photons and the triggering photons are always in phase, have the same polarization, and travel in the same direction. The probability of absorption of a photon is the same as the probability of stimulated emission, and so a majority of atoms must be in the metastable state to produce energy. Einstein back in 1917 was one of the important contributors to the understanding of stimulated emission of radiation. Among other things, Einstein was the first to realize that stimulated emission and absorption are equally probable. The laser acts as a temporary energy storage device that subsequently produces a massive energy output of single-wavelength, in-phase photons.

The name laser is an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation, the process just described. The process was proposed and developed following the advances in quantum physics. A joint Nobel Prize was awarded in 1964 to American Charles Townes (1915–), and Nikolay Basov (1922–2001) and Aleksandr Prokhorov (1916–2002), from the Soviet Union, for the development of lasers. The Nobel Prize in 1981 went to Arthur Schawlow (1921–1999) for pioneering laser applications. The original devices were called masers, because they produced microwaves. The first working laser was created in 1960 at Hughes Research labs (CA) by T. Maiman. It used a pulsed high-powered flash lamp and a ruby rod to produce red light. Today, the name laser is used for all such devices developed to produce a variety of wavelengths, including microwave, infrared, visible, and ultraviolet radiation. Figure 13.38 shows how a laser can be constructed to enhance the stimulated emission of radiation. Energy input can be from a flash tube, electrical discharge, or other sources, in a process sometimes called optical pumping. A large percentage of the original pumping energy is dissipated in other forms, but a population inversion must be achieved. Mirrors can be used to enhance stimulated emission by multiple passes of the radiation back and forth through the lasing material. One of the mirrors is semitransparent to allow some of the light to pass through. The laser output from a laser is a mere 1 percent of the light passing back and forth in a laser.

Real World Connections: Emission Spectrum

When observing an emission spectrum like the iron spectrum in Figure 13.15(b), you may notice the locations of the emission lines, which indicate the wavelength of each line. These wavelengths correspond to specific energy level differences for electrons in an iron atom. You may also notice that some of these emission lines are brighter than others, too.

This has to do with the probabilistic nature of emission. When an electron is in an excited state, for example in the n = 4 energy level of a hydrogen atom, it has a variety of possible options for emission. The electron can transition from n = 4 to n = 3, n = 2, or n = 1, but not all transitions are equally likely. Typically, transitions to lower energy states are much more probable than transitions to higher energy states.

This means photons corresponding to a transition from n = 4 to n = 3 are much less common than photons corresponding to a transition from n = 4 to n = 1. Thus, the emission line corresponding to the n = 4 to n = 1 transition is typically much brighter under ordinary circumstances. The probabilities can be affected by stimulation from outside photons, and this kind of interaction is at the heart of the laser—light amplification by the stimulated emission of radiation.

Lasers are constructed from many types of lasing materials, including gases, liquids, solids, and semiconductors. But all lasers are based on the existence of a metastable state or a phosphorescent material. Some lasers produce continuous output; others are pulsed in bursts as brief as Some laser outputs are fantastically powerful—some greater than —but the more common, everyday lasers produce something on the order of The helium-neon laser that produces a familiar red light is very common. Figure 13.39 shows the energy levels of helium and neon, a pair of noble gases that work well together. An electrical discharge is passed through a helium-neon gas mixture in which the number of atoms of helium is 10 times that of neon. The first excited state of helium is metastable and, thus, stores energy. This energy is easily transferred by collision to neon atoms, because they have an excited state at nearly the same energy as that in helium. That state in neon is also metastable, and this is the one that produces the laser output. The most likely transition is to the nearby state, producing 1.96-eV photons, which have a wavelength of 633 nm and appear red. A population inversion can be produced in neon, because there are so many more helium atoms and these put energy into the neon. Helium-neon lasers often have continuous output, because the population inversion can be maintained even while lasing occurs. Probably the most common lasers in use today, including the common laser pointer, are semiconductor or diode lasers, made of silicon. Here, energy is pumped into the material by passing a current in the device to excite the electrons. Special coatings on the ends and fine cleavings of the semiconductor material allow light to bounce back and forth and a tiny fraction to emerge as laser light. Diode lasers can usually run continually and produce outputs in the milliwatt range.

There are many medical applications of lasers. Lasers have the advantage that they can be focused to a small spot. They also have a well-defined wavelength. Many types of lasers are available today that provide wavelengths from the ultraviolet to the infrared. This is important, as one needs to be able to select a wavelength that will be preferentially absorbed by the material of interest. Objects appear a certain color because they absorb all other visible colors incident upon them. What wavelengths are absorbed depends upon the energy spacing between electron orbitals in that molecule. Unlike the hydrogen atom, biological molecules are complex and have a variety of absorption wavelengths or lines. But these can be determined and used in the selection of a laser with the appropriate wavelength. Water is transparent to the visible spectrum but will absorb light in the UV and IR regions. Blood—hemoglobin—strongly reflects red but absorbs most strongly in the UV.

Laser surgery uses a wavelength that is strongly absorbed by the tissue it is focused upon. One example of a medical application of lasers is shown in Figure 13.40. A detached retina can result in total loss of vision. Burns made by a laser focused to a small spot on the retina form scar tissue that can hold the retina in place, salvaging the patient’s vision. Other light sources cannot be focused as precisely as a laser due to refractive dispersion of different wavelengths. Similarly, laser surgery in the form of cutting or burning away tissue is made more accurate because laser output can be very precisely focused and is preferentially absorbed because of its single wavelength. Depending upon what part or layer of the retina needs repairing, the appropriate type of laser can be selected. For the repair of tears in the retina, a green argon laser is generally used. This light is absorbed well by tissues containing blood, so coagulation or welding of the tear can be done.

In dentistry, the use of lasers is rising. Lasers are most commonly used for surgery on the soft tissue of the mouth. They can be used to remove ulcers, stop bleeding, and reshape gum tissue. Their use in cutting into bones and teeth is not quite so common; here, the erbium YAG (yttrium aluminum garnet) laser is used.

The massive combination of lasers shown in Figure 13.41 can be used to induce nuclear fusion, the energy source of the sun and hydrogen bombs. Since lasers can produce very high power in very brief pulses, they can be used to focus an enormous amount of energy on a small glass sphere containing fusion fuel. Not only does the incident energy increase the fuel temperature significantly so that fusion can occur, but it also compresses the fuel to great density, enhancing the probability of fusion. The compression or implosion is caused by the momentum of the impinging laser photons.

Music CDs are now so common that vinyl records are quaint antiquities. CDs and DVDs store information digitally and have a much larger information-storage capacity than vinyl records. An entire encyclopedia can be stored on a single CD. Figure 13.42 illustrates how the information is stored and read from the CD. Pits made in the CD by a laser can be tiny and very accurately spaced to record digital information. These are read by having an inexpensive solid-state infrared laser beam scatter from pits as the CD spins, revealing their digital pattern and the information encoded upon them.

Holograms, such as those in Figure 13.43, are true three-dimensional images recorded on film by lasers. Holograms are used for amusement, decoration on novelty items and magazine covers, security on credit cards and driver’s licenses—a laser and other equipment is needed to reproduce them—and for serious three-dimensional information storage. You can see that a hologram is a true three-dimensional image, because objects change relative position in the image when viewed from different angles.

The name hologram means entire picture from the Greek holo, as in holistic, because the image is three-dimensional. Holography is the process of producing holograms and, although they are recorded on photographic film, the process is quite different from normal photography. Holography uses light interference or wave optics, whereas normal photography uses geometric optics. Figure 13.44 shows one method of producing a hologram. Coherent light from a laser is split by a mirror, with part of the light illuminating the object. The remainder, called the reference beam, shines directly on a piece of film. Light scattered from the object interferes with the reference beam, producing constructive and destructive interference. As a result, the exposed film looks foggy, but close examination reveals a complicated interference pattern stored on it. Where the interference was constructive, the film—a negative actually—is darkened. Holography is sometimes called lensless photography, because it uses the wave characteristics of light as contrasted to normal photography, which uses geometric optics and so requires lenses.

Light falling on a hologram can form a three-dimensional image. The process is complicated in detail, but the basics can be understood as shown in Figure 13.45, in which a laser of the same type that exposed the film is now used to illuminate it. The myriad tiny exposed regions of the film are dark and block the light, while less-exposed regions allow light to pass. The film thus acts much like a collection of diffraction gratings with various spacings. Light passing through the hologram is diffracted in various directions, producing both real and virtual images of the object used to expose the film. The interference pattern is the same as that produced by the object. Moving your eye to various places in the interference pattern gives you different perspectives, just as looking directly at the object would. The image thus looks like the object and is three-dimensional like the object.

The hologram illustrated in Figure 13.45 is a transmission hologram. Holograms that are viewed with reflected light, such as the white light holograms on credit cards, are reflection holograms and are more common. White light holograms often appear a little blurry with rainbow edges, because the diffraction patterns of various colors of light are at slightly different locations due to their different wavelengths. Further uses of holography include all types of three-dimensional information storage, such as of statues in museums and engineering studies of structures and three-dimensional images of human organs. Invented in the late 1940s by Dennis Gabor (1900–1970), who won the 1971 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work, holography became far more practical with the development of the laser. Since lasers produce coherent single-wavelength light, their interference patterns are more pronounced. The precision is so great that it is even possible to record numerous holograms on a single piece of film by just changing the angle of the film for each successive image. This is how the holograms that move as you walk by them are produced—a kind of lensless movie.

In a similar way, in the medical field, holograms have allowed complete three-dimensional holographic displays of objects from a stack of images. Storing these images for future use is relatively easy. With the use of an endoscope, high-resolution three-dimensional holographic images of internal organs and tissues can be made.