Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Define X-ray tube and its spectrum

- Show the X-ray characteristic energy

- Specify the use of X-rays in medical observations

- Explain the use of X-rays in CT scanners in diagnostics

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

- 5.B.8.1 The student is able to describe emission or absorption spectra associated with electronic or nuclear transitions as transitions between allowed energy states of the atom in terms of the principle of energy conservation, including characterization of the frequency of radiation emitted or absorbed. (S.P. 1.2, 7.2)

Each type of atom or element has its own characteristic electromagnetic spectrum. X-rays lie at the high-frequency end of an atom’s spectrum and are characteristic of the atom as well. In this section, we explore characteristic X-rays and some of their important applications.

We have previously discussed X-rays as a part of the electromagnetic spectrum in Photon Energies and the Electromagnetic Spectrum. That module illustrated how an X-ray tube—a specialized CRT—produces X-rays. Electrons emitted from a hot filament are accelerated with a high voltage, gaining significant kinetic energy and striking the anode.

There are two processes by which X-rays are produced in the anode of an X-ray tube. In one process, the deceleration of electrons produces X-rays, and these X-rays are called bremsstrahlung, or braking radiation. The second process is atomic in nature and produces characteristic X-rays, so called because they are characteristic of the anode material. The X-ray spectrum in Figure 13.22 is typical of what is produced by an X-ray tube, showing a broad curve of bremsstrahlung radiation with characteristic X-ray peaks on it.

The spectrum in Figure 13.22 is collected over a period of time in which many electrons strike the anode, with a variety of possible outcomes for each hit. The broad range of X-ray energies in the bremsstrahlung radiation indicates that an incident electron’s energy is not usually converted entirely into photon energy. The highest-energy X-ray produced is one for which all of the electron’s energy was converted to photon energy. Thus the accelerating voltage and the maximum X-ray energy are related by conservation of energy. Electric potential energy is converted to kinetic energy and then to photon energy, so that Units of electron volts are convenient. For example, a 100-kV accelerating voltage produces X-ray photons with a maximum energy of 100 keV.

Some electrons excite atoms in the anode. Part of the energy that they deposit by collision with an atom results in one or more of the atom’s inner electrons being knocked into a higher orbit or the atom being ionized. When the anode’s atoms de-excite, they emit characteristic electromagnetic radiation. The most energetic of these are produced when an inner-shell vacancy is filled—that is, when an or shell electron has been excited to a higher level, and another electron falls into the vacant spot. A characteristic X-ray (see Photon Energies and the Electromagnetic Spectrum) is EM radiation emitted by an atom when an inner-shell vacancy is filled. Figure 13.23 shows a representative energy-level diagram that illustrates the labeling of characteristic X-rays. X-rays created when an electron falls into an shell vacancy are called when they come from the next higher level; that is, an to transition. The labels come from the older alphabetical labeling of shells starting with rather than using the principal quantum numbers 1, 2, 3, . . . . A more energetic X-ray is produced when an electron falls into an shell vacancy from the shell, that is, an to transition. Similarly, when an electron falls into the shell from the shell, an X-ray is created. The energies of these X-rays depend on the energies of electron states in the particular atom and, thus, are characteristic of that element: every element has it own set of X-ray energies. This property can be used to identify elements, for example, to find trace—small—amounts of an element in an environmental or biological sample.

Example 13.2 Characteristic X-ray Energy

Calculate the approximate energy of a X-ray from a tungsten anode in an X-ray tube.

Strategy

How do we calculate energies in a multiple-electron atom? In the case of characteristic X-rays, the following approximate calculation is reasonable. Characteristic X-rays are produced when an inner-shell vacancy is filled. Inner-shell electrons are nearer the nucleus than others in an atom and thus feel little net effect from the others. This is similar to what happens inside a charged conductor, where its excess charge is distributed over the surface so that it produces no electric field inside. It is reasonable to assume the inner-shell electrons have hydrogen-like energies, as given by

Solution

gives the orbital energies for hydrogen-like atoms to be where As noted, the effective is 73. Now the X-ray energy is given by

where

and

Thus

Discussion

This large photon energy is typical of characteristic X-rays from heavy elements. It is large compared with other atomic emissions because it is produced when an inner-shell vacancy is filled, and inner-shell electrons are tightly bound. Characteristic X-ray energies become progressively larger for heavier elements because their energy increases approximately as Significant accelerating voltage is needed to create these inner-shell vacancies. In the case of tungsten, at least 72.5 kV is needed, because other shells are filled and you cannot simply bump one electron to a higher filled shell. Tungsten is a common anode material in X-ray tubes; so much of the energy of the impinging electrons is absorbed, raising its temperature, that a high-melting-point material like tungsten is required.

Medical and Other Diagnostic Uses of X-rays

Medical and Other Diagnostic Uses of X-rays

All of us can identify diagnostic uses of X-ray photons. Among these are the universal dental and medical X-rays that have become an essential part of medical diagnostics (see Figure 13.25 and Figure 13.26). X-rays are also used to inspect our luggage at airports, as shown in Figure 13.24, and for early detection of cracks in crucial aircraft components. An X-ray is not only a noun meaning high-energy photon, it also is an image produced by X-rays, and it has been made into a familiar verb—to be X-rayed.

The most common X-ray images are simple shadows. Since X-ray photons have high energies, they penetrate materials that are opaque to visible light. The more energy an X-ray photon has, the more material it will penetrate. So an X-ray tube may be operated at 50.0 kV for a chest X-ray, whereas it may need to be operated at 100 kV to examine a broken leg in a cast. The depth of penetration is related to the density of the material as well as to the energy of the photon. The denser the material, the fewer X-ray photons get through and the darker the shadow. Thus X-rays excel at detecting breaks in bones and in imaging other physiological structures, that differ in density from surrounding material. Because of their high photon energy, X-rays produce significant ionization in materials and damage cells in biological organisms. Modern uses minimize exposure to the patient and eliminate exposure to others. Biological effects of X-rays will be explored in the next chapter along with other types of ionizing radiation such as those produced by nuclei.

As the X-ray energy increases, the Compton effect (see Photon Momentum) becomes more important in the attenuation of the X-rays. Here, the X-ray scatters from an outer electron shell of the atom, giving the ejected electron some kinetic energy while losing energy itself. The probability for attenuation of the X-rays depends upon the number of electrons present—the material’s density—as well as the thickness of the material. Chemical composition of the medium, as characterized by its atomic number is not important here. Low-energy X-rays provide better contrast—sharper images. However, due to greater attenuation and less scattering, they are more absorbed by thicker materials. Greater contrast can be achieved by injecting a substance with a large atomic number, such as barium or iodine. The structure of the part of the body that contains the substance, for example, the gastro-intestinal tract or the abdomen, can easily be seen this way.

A standard X-ray gives only a two-dimensional view of the object. Dense bones might hide images of soft tissue or organs. If you took another X-ray from the side of the person—the first one being from the front—you would gain additional information. While shadow images are sufficient in many applications, far more sophisticated images can be produced with modern technology. Figure 13.27 shows the use of a computed tomography (CT) scanner, also called computed axial tomography (CAT) scanner. X-rays are passed through a narrow section, called a slice, of the patient’s body, or body part, over a range of directions. An array of many detectors on the other side of the patient registers the X-rays. The system is then rotated around the patient and another image is taken, and so on. The X-ray tube and detector array are mechanically attached and so rotate together. Complex computer image processing of the relative absorption of the X-rays along different directions produces a highly detailed image. Different slices are taken as the patient moves through the scanner on a table. Multiple images of different slices can also be computer analyzed to produce three-dimensional information, sometimes enhancing specific types of tissue, as shown in Figure 13.28. G. Hounsfield (UK) and A. Cormack (United States) won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1979 for their development of CT.

X-Ray Diffraction and Crystallography

X-Ray Diffraction and Crystallography

Since X-ray photons are very energetic, they have relatively short wavelengths. For example, the 54.4-keV X-ray of Example 13.2 has a wavelength Thus, typical X-ray photons act like rays when they encounter macroscopic objects, like teeth, and produce sharp shadows; however, since atoms are on the order of 0.1 nm in size, X-rays can be used to detect the location, shape, and size of atoms and molecules. The process is called X-ray diffraction, because it involves the diffraction and interference of X-rays to produce patterns that can be analyzed for information about the structures that scattered the X-rays. Perhaps the most famous example of X-ray diffraction is the discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953 by an international team of scientists working at the Cavendish Laboratory—American James Watson, Englishman Francis Crick, and New Zealand–born Maurice Wilkins. Using X-ray diffraction data produced by Rosalind Franklin, they were the first to discern the structure of DNA that is so crucial to life. For this, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. There is much debate and controversy over the issue that Rosalind Franklin was not included in the prize.

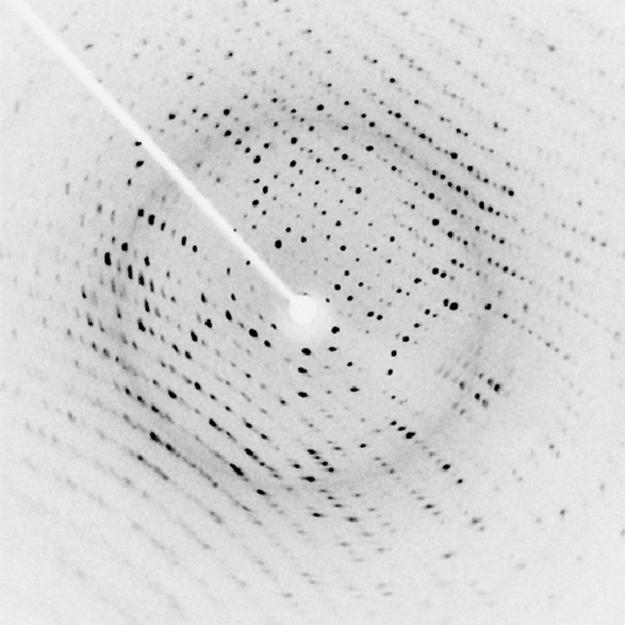

Figure 13.29 shows a diffraction pattern produced by the scattering of X-rays from a crystal. This process is known as X-ray crystallography because of the information it can yield about crystal structure, and it was the type of data Rosalind Franklin supplied to Watson and Crick for DNA. Not only do X-rays confirm the size and shape of atoms, they give information on the atomic arrangements in materials. For example, current research in high-temperature superconductors involves complex materials whose lattice arrangements are crucial to obtaining a superconducting material. These can be studied using X-ray crystallography.

Historically, the scattering of X-rays from crystals was used to prove that X-rays are energetic EM waves. This was suspected from the time of the discovery of X-rays in 1895, but it was not until 1912 that the German Max von Laue (1879–1960) convinced two of his colleagues to scatter X-rays from crystals. If a diffraction pattern is obtained, he reasoned, then the X-rays must be waves, and their wavelength could be determined. The spacing of atoms in various crystals was reasonably well known at the time, based on good values for Avogadro’s number. The experiments were convincing, and the 1914 Nobel Prize in Physics was given to von Laue for his suggestion leading to the proof that X-rays are EM waves. In 1915, the unique father-and-son team of Sir William Henry Bragg and his son Sir William Lawrence Bragg were awarded a joint Nobel Prize for inventing the X-ray spectrometer and the then-new science of X-ray analysis. The elder Bragg had migrated to Australia from England just after graduating in mathematics. He learned physics and chemistry during his career at the University of Adelaide. The younger Bragg was born in Adelaide but went back to the Cavendish Laboratories in England to a career in X-ray and neutron crystallography; he provided support for Watson, Crick, and Wilkins for their work on unraveling the mysteries of DNA and to Max Perutz for his 1962 Nobel Prize-winning work on the structure of hemoglobin. Here again, we witness the enabling nature of physics—establishing instruments and designing experiments as well as solving mysteries in the biomedical sciences.

Certain other uses for X-rays will be studied in later chapters. X-rays are useful in the treatment of cancer because of the inhibiting effect they have on cell reproduction. X-rays observed coming from outer space are useful in determining the nature of their sources, such as neutron stars and possibly black holes. Created in nuclear bomb explosions, X-rays can also be used to detect clandestine atmospheric tests of these weapons. X-rays can cause excitations of atoms, which then fluoresce—emitting characteristic EM radiation—making X-ray-induced fluorescence a valuable analytical tool in a range of fields from art to archaeology.