Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Define X-ray tube and its spectrum

- Show the X-ray characteristic energy

- Specify the use of X-rays in medical observations

- Explain the use of X-rays in CT scanners in diagnostics

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

- 5.B.8.1 The student is able to describe emission or absorption spectra associated with electronic or nuclear transitions as transitions between allowed energy states of the atom in terms of the principle of energy conservation, including characterization of the frequency of radiation emitted or absorbed. (S.P. 1.2, 7.2)

Each type of atom or element has its own characteristic electromagnetic spectrum. X-rays lie at the high-frequency end of an atom’s spectrum and are characteristic of the atom as well. In this section, we explore characteristic X-rays and some of their important applications.

We have previously discussed X-rays as a part of the electromagnetic spectrum in Photon Energies and the Electromagnetic Spectrum. That module illustrated how an X-ray tube—a specialized CRT—produces X-rays. Electrons emitted from a hot filament are accelerated with a high voltage, gaining significant kinetic energy and striking the anode.

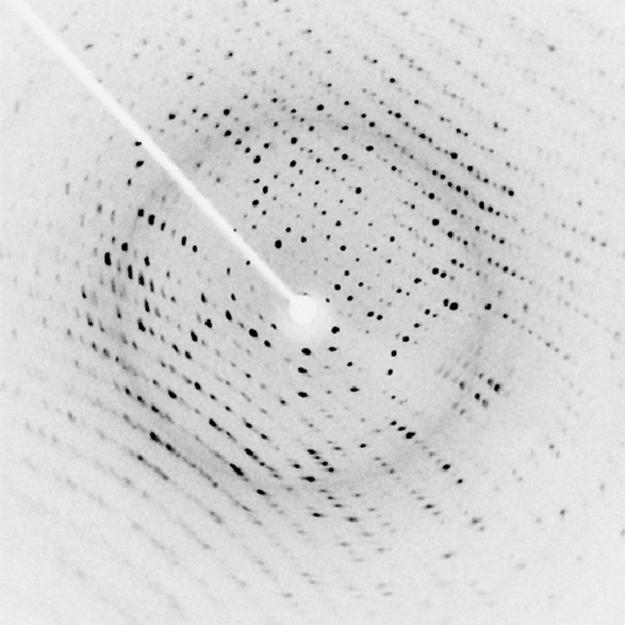

There are two processes by which X-rays are produced in the anode of an X-ray tube. In one process, the deceleration of electrons produces X-rays, and these X-rays are called bremsstrahlung, or braking radiation. The second process is atomic in nature and produces characteristic X-rays, so called because they are characteristic of the anode material. The X-ray spectrum in Figure 13.22 is typical of what is produced by an X-ray tube, showing a broad curve of bremsstrahlung radiation with characteristic X-ray peaks on it.

The spectrum in Figure 13.22 is collected over a period of time in which many electrons strike the anode, with a variety of possible outcomes for each hit. The broad range of X-ray energies in the bremsstrahlung radiation indicates that an incident electron’s energy is not usually converted entirely into photon energy. The highest-energy X-ray produced is one for which all of the electron’s energy was converted to photon energy. Thus the accelerating voltage and the maximum X-ray energy are related by conservation of energy. Electric potential energy is converted to kinetic energy and then to photon energy, so that Units of electron volts are convenient. For example, a 100-kV accelerating voltage produces X-ray photons with a maximum energy of 100 keV.

Some electrons excite atoms in the anode. Part of the energy that they deposit by collision with an atom results in one or more of the atom’s inner electrons being knocked into a higher orbit or the atom being ionized. When the anode’s atoms de-excite, they emit characteristic electromagnetic radiation. The most energetic of these are produced when an inner-shell vacancy is filled—that is, when an or shell electron has been excited to a higher level, and another electron falls into the vacant spot. A characteristic X-ray (see Photon Energies and the Electromagnetic Spectrum) is EM radiation emitted by an atom when an inner-shell vacancy is filled. Figure 13.23 shows a representative energy-level diagram that illustrates the labeling of characteristic X-rays. X-rays created when an electron falls into an shell vacancy are called when they come from the next higher level; that is, an to transition. The labels come from the older alphabetical labeling of shells starting with rather than using the principal quantum numbers 1, 2, 3, . . . . A more energetic X-ray is produced when an electron falls into an shell vacancy from the shell, that is, an to transition. Similarly, when an electron falls into the shell from the shell, an X-ray is created. The energies of these X-rays depend on the energies of electron states in the particular atom and, thus, are characteristic of that element: every element has it own set of X-ray energies. This property can be used to identify elements, for example, to find trace—small—amounts of an element in an environmental or biological sample.

Example 13.2 Characteristic X-ray Energy

Calculate the approximate energy of a X-ray from a tungsten anode in an X-ray tube.

Strategy

How do we calculate energies in a multiple-electron atom? In the case of characteristic X-rays, the following approximate calculation is reasonable. Characteristic X-rays are produced when an inner-shell vacancy is filled. Inner-shell electrons are nearer the nucleus than others in an atom and thus feel little net effect from the others. This is similar to what happens inside a charged conductor, where its excess charge is distributed over the surface so that it produces no electric field inside. It is reasonable to assume the inner-shell electrons have hydrogen-like energies, as given by

Solution

gives the orbital energies for hydrogen-like atoms to be where As noted, the effective is 73. Now the X-ray energy is given by

where

and

Thus

Discussion

This large photon energy is typical of characteristic X-rays from heavy elements. It is large compared with other atomic emissions because it is produced when an inner-shell vacancy is filled, and inner-shell electrons are tightly bound. Characteristic X-ray energies become progressively larger for heavier elements because their energy increases approximately as Significant accelerating voltage is needed to create these inner-shell vacancies. In the case of tungsten, at least 72.5 kV is needed, because other shells are filled and you cannot simply bump one electron to a higher filled shell. Tungsten is a common anode material in X-ray tubes; so much of the energy of the impinging electrons is absorbed, raising its temperature, that a high-melting-point material like tungsten is required.