Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the effects of the magnetic force between two conductors

- Calculate the force between two parallel conductors

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

- 2.D.2.1 The student is able to create a verbal or visual representation of a magnetic field around a long straight wire or a pair of parallel wires. (S.P. 1.1)

- 3.C.3.1 The student is able to use right-hand rules to analyze a situation involving a current-carrying conductor and a moving electrically charged object to determine the direction of the magnetic force exerted on the charged object due to the magnetic field created by the current-carrying conductor. (S.P. 1.4)

You might expect that there are significant forces between current-carrying wires because ordinary currents produce significant magnetic fields and these fields exert significant forces on ordinary currents. But you might not expect that the force between wires is used to define the ampere. It might also surprise you to learn that this force has something to do with why large circuit breakers burn up when they attempt to interrupt large currents.

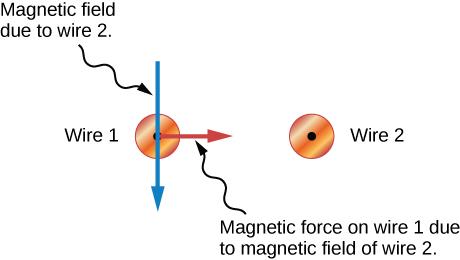

The force between two long straight and parallel conductors separated by a distance can be found by applying what we have developed in preceding sections. Figure 5.35 shows the wires, their currents, the fields they create, and the subsequent forces they exert on one another. Let us consider the field produced by wire 1 and the force it exerts on wire 2 (call the force The field due to at a distance is given to be

This field is uniform along wire 2 and perpendicular to it, and so the force it exerts on wire 2 is given by with

By Newton’s third law, the forces on the wires are equal in magnitude, and so we just write for the magnitude of (Note that Because the wires are very long, it is convenient to think in terms of the force per unit length. Substituting the expression for into the last equation and rearranging terms gives

is the force per unit length between two parallel currents and separated by a distance The force is attractive if the currents are in the same direction and repulsive if they are in opposite directions.

Making Connections: Field Canceling

For two parallel wires, the fields will tend to cancel out in the area between the wires.

Note that the magnetic influence of the wire on the left-hand side extends beyond the wire on the right-hand side. To the right of both wires, the total magnetic field is directed toward the top of the page and is the result of the sum of the fields of both wires. Obviously, the closer wire has a greater effect on the overall magnetic field, but the more distant wire also contributes. One wire cannot block the magnetic field of another wire any more than a massive stone floor beneath you can block the gravitational field of Earth.

Parallel wires with currents in the same direction attract, as you can see if we isolate the magnetic field lines of wire 2 influencing the current in wire 1. RHR-1 tells us the direction of the resulting magnetic force.

When the currents point in opposite directions as shown, the magnetic field in between the two wires is augmented. In the region outside of the two wires, along the horizontal line connecting the wires, the magnetic fields partially cancel.

Parallel wires with currents in opposite directions repel, as you can see if we isolate the magnetic field lines of wire 2 influencing the current in wire 1. RHR-1 tells us the direction of the resulting magnetic force.

This force is responsible for the pinch effect in electric arcs and plasmas. The force exists whether the currents are in wires or not. In an electric arc, where currents are moving parallel to one another, there is an attraction that squeezes currents into a smaller tube. In large circuit breakers, like those used in neighborhood power distribution systems, the pinch effect can concentrate an arc between plates of a switch trying to break a large current, burn holes, and even ignite the equipment. Another example of the pinch effect is found in the solar plasma, where jets of ionized material, such as solar flares, are shaped by magnetic forces.

The operational definition of the ampere is based on the force between current-carrying wires. Note that for parallel wires separated by 1 meter with each carrying 1 ampere, the force per meter is

Since is exactly by definition, and because the force per meter is exactly This is the basis of the operational definition of the ampere.

The Ampere

The official definition of the ampere is as follows:

One ampere of current through each of two parallel conductors of infinite length, separated by one meter in empty space free of other magnetic fields, causes a force of exactly on each conductor.

Infinite-length straight wires are impractical and so, in practice, a current balance is constructed with coils of wire separated by a few centimeters. Force is measured to determine current. This also provides us with a method for measuring the coulomb. We measure the charge that flows for a current of one ampere in one second. That is, For both the ampere and the coulomb, the method of measuring force between conductors is the most accurate in practice.