Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the effects of a magnetic field on a moving charge

- Calculate the radius of curvature of the path of a charge that is moving in a magnetic field

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

- 3.C.3.1 The student is able to use right-hand rules to analyze a situation involving a current-carrying conductor and a moving electrically charged object to determine the direction of the magnetic force exerted on the charged object due to the magnetic field created by the current-carrying conductor. (S.P. 1.4)

Magnetic force can cause a charged particle to move in a circular or spiral path. Cosmic rays are energetic charged particles in outer space, some of which approach Earth. They can be forced into spiral paths by Earth’s magnetic field. Protons in giant accelerators are kept in a circular path by magnetic force. The bubble chamber photograph in Figure 5.11 shows charged particles moving in such curved paths. The curved paths of charged particles in magnetic fields are the basis of a number of phenomena and can even be used analytically, such as in a mass spectrometer.

So does the magnetic force cause circular motion? Magnetic force is always perpendicular to velocity, so that it does no work on the charged particle. The particle’s kinetic energy and speed thus remain constant. The direction of motion is affected, but not the speed. This is typical of uniform circular motion. The simplest case occurs when a charged particle moves perpendicular to a uniform field, such as shown in Figure 5.12. (If this takes place in a vacuum, the magnetic field is the dominant factor determining the motion.) Here, the magnetic force supplies the centripetal force Noting that we see that

Because the magnetic force supplies the centripetal force we have

Solving for yields

Here, is the radius of curvature of the path of a charged particle with mass and charge moving at a speed perpendicular to a magnetic field of strength If the velocity is not perpendicular to the magnetic field, then is the component of the velocity perpendicular to the field. The component of the velocity parallel to the field is unaffected, because the magnetic force is zero for motion parallel to the field. This produces a spiral motion rather than a circular one.

Example 5.2 Calculating the Curvature of the Path of an Electron Moving in a Magnetic Field: A Magnet on a TV Screen

A magnet brought near an old-fashioned TV screen such as in Figure 5.13 (TV sets with cathode ray tubes instead of LCD screens) severely distorts its picture by altering the path of the electrons that make its phosphors glow. (Don’t try this at home, as it will permanently magnetize and ruin the TV.) To illustrate this, calculate the radius of curvature of the path of an electron having a velocity of (corresponding to the accelerating voltage of about 10.0 kV used in some TVs) perpendicular to a magnetic field of strength (obtainable with permanent magnets).

Strategy

We can find the radius of curvature directly from the equation since all other quantities in it are given or known.

Solution

Using known values for the mass and charge of an electron, along with the given values of and gives us

or

Discussion

The small radius indicates a large effect. The electrons in the TV picture tube are made to move in very tight circles, greatly altering their paths and distorting the image.

Figure 5.14 shows how electrons not moving perpendicular to magnetic field lines follow the field lines. The component of velocity parallel to the lines is unaffected, and so the charges spiral along the field lines. If field strength increases in the direction of motion, the field will exert a force to slow the charges, forming a kind of magnetic mirror, as shown below.

The properties of charged particles in magnetic fields are related to such different things as the Aurora Australis or Aurora Borealis and particle accelerators. Charged particles approaching magnetic field lines may get trapped in spiral orbits about the lines rather than crossing them, as seen above. Some cosmic rays, for example, follow Earth’s magnetic field lines, entering the atmosphere near the magnetic poles and causing the southern or northern lights through their ionization of molecules in the atmosphere. This glow of energized atoms and molecules is seen in Figure 5.1. Those particles that approach middle latitudes must cross magnetic field lines, and many are prevented from penetrating the atmosphere. Cosmic rays are a component of background radiation; consequently, they give a higher radiation dose at the poles than at the equator.

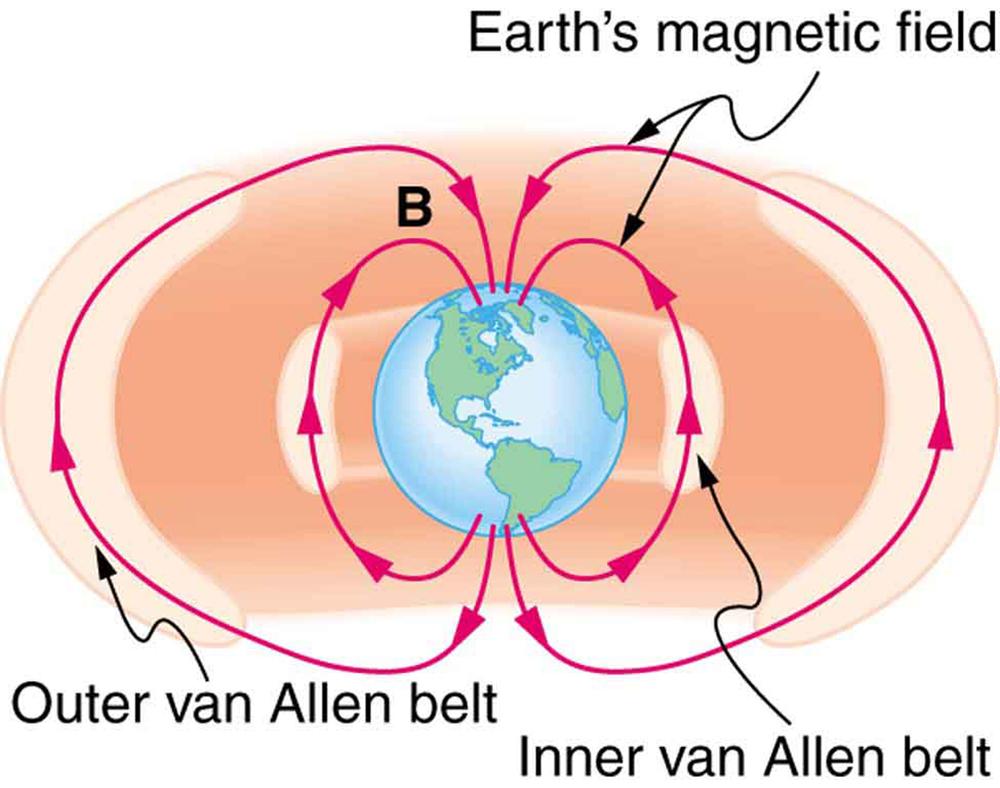

Some incoming charged particles become trapped in Earth’s magnetic field, forming two belts above the atmosphere known as the Van Allen radiation belts after the discoverer James A. Van Allen, an American astrophysicist. (See Figure 5.16.) Particles trapped in these belts form radiation fields (similar to nuclear radiation) so intense that manned space flights avoid them and satellites with sensitive electronics are kept out of them. In the few minutes it took lunar missions to cross the Van Allen radiation belts, astronauts received radiation doses more than twice the allowed annual exposure for radiation workers. Other planets have similar belts, especially those having strong magnetic fields like Jupiter.

Back on Earth, we have devices that employ magnetic fields to contain charged particles. Among them are the giant particle accelerators that have been used to explore the substructure of matter. (See Figure 5.17.) Magnetic fields not only control the direction of the charged particles, they also are used to focus particles into beams and overcome the repulsion of like charges in these beams.

Thermonuclear fusion (like that occurring in the sun) is a hope for a future clean energy source. One of the most promising devices is the tokamak, which uses magnetic fields to contain (or trap) and direct the reactive charged particles. (See Figure 5.18.) Less exotic, but more immediately practical, amplifiers in microwave ovens use a magnetic field to contain oscillating electrons. These oscillating electrons generate the microwaves sent into the oven.

Mass spectrometers have a variety of designs, and many use magnetic fields to measure mass. The curvature of a charged particle’s path in the field is related to its mass and is measured to obtain mass information. (See More Applications of Magnetism.) Historically, such techniques were used in the first direct observations of electron charge and mass. Today, mass spectrometers (sometimes coupled with gas chromatographs) are used to determine the make-up and sequencing of large biological molecules.