General Relativity

Einstein first considered the case of no observer acceleration when he developed the revolutionary special theory of relativity, publishing his first work on it in 1905. By 1916, he laid the foundation of general relativity, again almost on his own. Much of what Einstein did to develop his ideas was to mentally analyze certain carefully and clearly defined situations—doing this is to perform a thought experiment. Figure 17.10 illustrates a thought experiment, like the ones that convinced Einstein that light must fall in a gravitational field. Think about what a person feels in an elevator that is accelerated upward. It is identical to being in a stationary elevator in a gravitational field. The feet of a person are pressed against the floor, and objects released from a hand fall with identical accelerations. In fact, it is not possible, without looking outside, to know what is happening—acceleration upward or gravity. This led Einstein to correctly postulate that acceleration and gravity will produce identical effects in all situations. So, if acceleration affects light, then gravity will, too. Figure 17.10 also shows the effect of acceleration on a beam of light shone horizontally at one wall. Since the accelerated elevator moves up during the time light travels across the elevator, the beam of light strikes low, seeming to the person to bend down. Normally a tiny effect, since the speed of light is so great. The same effect must occur due to gravity, Einstein reasoned, since there is no way to tell the effects of gravity acting downward from acceleration of the elevator upward. Thus, gravity affects the path of light, even though we think of gravity as acting between masses and photons are massless.

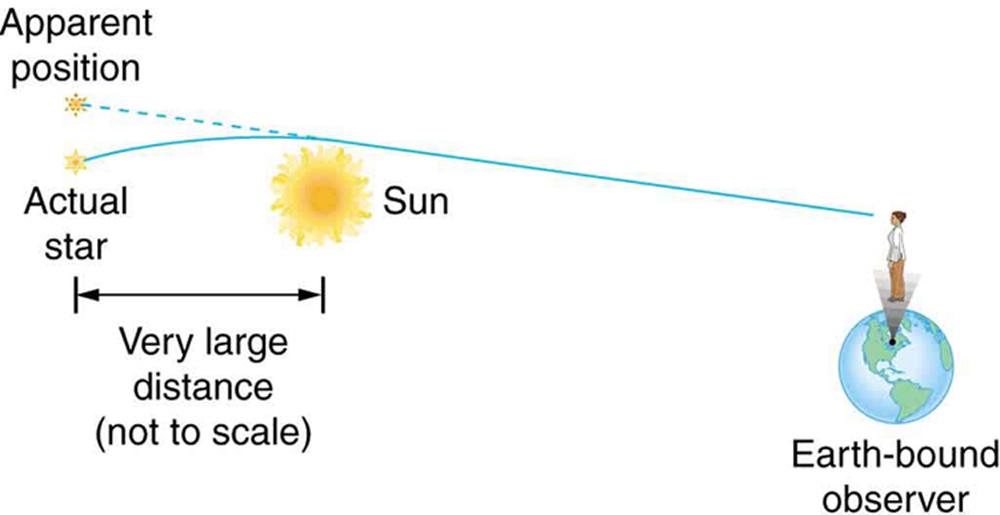

Einstein's theory of general relativity got its first verification in 1919 when starlight passing near the sun was observed during a solar eclipse. (See Figure 17.11.) During an eclipse, the sky is darkened and we can briefly see stars. Those in a line of sight nearest the sun should have a shift in their apparent positions. Not only was this shift observed, but it agreed with Einstein's predictions well within experimental uncertainties. This discovery created a scientific and public sensation. Einstein was now a folk hero as well as a very great scientist. The bending of light by matter is equivalent to a bending of space itself, with light following the curve. This is another radical change in our concept of space and time. It is also another connection that any particle with mass or energy—such as a massless photon—is affected by gravity.

There are several current forefront efforts related to general relativity. One is the observation and analysis of gravitational lensing of light. Another is analysis of the definitive proof of the existence of black holes. Direct observation of gravitational waves or moving wrinkles in space is being searched for. Theoretical efforts are also being aimed at the possibility of time travel and wormholes into other parts of space due to black holes.

Gravitational lensingAs you can see in Figure 17.11, light is bent toward a mass, producing an effect much like a converging lens—large masses are needed to produce observable effects. On a galactic scale, the light from a distant galaxy could be lensed into several images when passing close by another galaxy on its way to Earth. Einstein predicted this effect, but he considered it unlikely that we would ever observe it. A number of cases of this effect have now been observed; one is shown in Figure 17.12. This effect is a much larger scale verification of general relativity. But such gravitational lensing is also useful in verifying that the red shift is proportional to distance. The red shift of the intervening galaxy is always less than that of the one being lensed, and each image of the lensed galaxy has the same red shift. This verification supplies more evidence that red shift is proportional to distance. Confidence that the multiple images are not different objects is bolstered by the observations that if one image varies in brightness over time, the others also vary in the same manner.

Black holes are objects having such large gravitational fields that things can fall in, but nothing, not even light, can escape. Bodies, like Earth or the sun, have what is called an escape velocity. If an object moves straight up from the body, starting at the escape velocity, it will just be able to escape the gravity of the body. The greater the acceleration of gravity on the body, the greater is the escape velocity. As long ago as the late 1700s, it was proposed that if the escape velocity is greater than the speed of light, then light cannot escape. Simon Laplace (1749–1827), the French astronomer and mathematician, even incorporated this idea of a dark star into his writings. But the idea was dropped after Young's double slit experiment showed light to be a wave. For some time, light was thought not to have particle characteristics and, thus, could not be acted upon by gravity. The idea of a black hole was very quickly reincarnated in 1916 after Einstein's theory of general relativity was published. It is now thought that black holes can form in the supernova collapse of a massive star, forming an object perhaps 10 km across and having a mass greater than that of our sun. It is interesting that several prominent physicists who worked on the concept, including Einstein, firmly believed that nature would find a way to prohibit such objects.

Black holes are difficult to observe directly, because they are small and no light comes directly from them. In fact, no light comes from inside the event horizon, which is defined to be at a distance from the object at which the escape velocity is exactly the speed of light. The radius of the event horizon is known as the Schwarzschild radius and is given by

17.2 where is the universal gravitational constant, is the mass of the body, and is the speed of light. The event horizon is the edge of the black hole and is its radius, that is, the size of a black hole is twice Since is small and is large, you can see that black holes are extremely small, only a few kilometers for masses a little greater than the sun's. The object itself is inside the event horizon.

Physics near a black hole is fascinating. Gravity increases so rapidly that, as you approach a black hole, the tidal effects tear matter apart, with matter closer to the hole being pulled in with much more force than that only slightly farther away. This can pull a companion star apart and heat inflowing gases to the point of producing X-rays. (See Figure 17.13.) We have observed X-rays from certain binary star systems that are consistent with such a picture. This is not quite proof of black holes, because the X-rays could also be caused by matter falling onto a neutron star. These objects were first discovered in 1967 by the British astrophysicists Jocelyn Bell and Anthony Hewish. Neutron stars are literally stars composed of neutrons. They are formed by the collapse of a star's core in a supernova, during which electrons and protons are forced together to form neutrons (the reverse of neutron decay). Neutron stars are slightly larger than a black hole of the same mass and will not collapse further because of resistance by the strong force. However, neutron stars cannot have a mass greater than about eight solar masses or they must collapse to a black hole. With recent improvements in our ability to resolve small details, such as with the orbiting Chandra X-ray Observatory, it has become possible to measure the masses of X-ray-emitting objects by observing the motion of companion stars and other matter in their vicinity. What has emerged is a plethora of X-ray-emitting objects too massive to be neutron stars. This evidence is considered conclusive and the existence of black holes is widely accepted. These black holes are concentrated near galactic centers.

We also have evidence that supermassive black holes may exist at the cores of many galaxies, including the Milky Way. Such a black hole might have a mass millions or even billions of times that of the sun, and it would probably have formed when matter first coalesced into a galaxy billions of years ago. Supporting this is the fact that very distant galaxies are more likely to have abnormally energetic cores. Some of the moderately distant galaxies, and hence among the younger, are known as quasars and emit as much or more energy than a normal galaxy, but from a region less than a light year across. Quasar energy outputs may vary in times less than a year, so that the energy-emitting region must be less than a light year across. The best explanation of quasars is that they are young galaxies with a supermassive black hole forming at their core, and that they become less energetic over billions of years. In closer superactive galaxies, we observe tremendous amounts of energy being emitted from very small regions of space, consistent with stars falling into a black hole at the rate of one or more a month. The Hubble Space Telescope (1994) observed an accretion disk in the galaxy M87 rotating rapidly around a region of extreme energy emission. (See Figure 17.13.) A jet of material being ejected perpendicular to the plane of rotation gives further evidence of a supermassive black hole as the engine.

Gravitational wavesIf a massive object distorts the space around it, like the foot of a water bug on the surface of a pond, then movement of the massive object should create waves in space, like those on a pond. Gravitational waves are mass-created distortions in space that propagate at the speed of light and are predicted by general relativity. Since gravity is by far the weakest force, extreme conditions are needed to generate significant gravitational waves. Gravity near binary neutron star systems is so great that significant gravitational wave energy is radiated as the two neutron stars orbit one another. American astronomers, Joseph Taylor and Russell Hulse, measured changes in the orbit of such a binary neutron star system. They found its orbit to change precisely as predicted by general relativity, a strong indication of gravitational waves; and, they were awarded the 1993 Nobel Prize. But direct detection of gravitational waves on Earth would be conclusive. For many years, various attempts have been made to detect gravitational waves by observing vibrations induced in matter distorted by these waves. American physicist Joseph Weber pioneered this field in the 1960s, but no conclusive events have been observed. No gravity wave detectors were in operation at the time of the 1987A supernova, unfortunately. There are now several ambitious systems of gravitational wave detectors in use around the world. These include the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) system with two laser interferometer detectors, one in the state of Washington and another in Louisiana (see Figure 17.15), and the VIRGO (Variability of Irradiance and Gravitational Oscillations) facility in Italy with a single detector.